|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

| MERC home > mercury in fish |

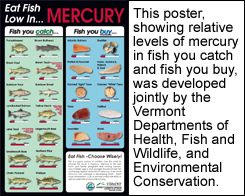

Mercury in FishHuman Exposure to Mercury Due to Fish ConsumptionMercury emissions from natural and anthropogenic sources enter the global mercury cycle and are distributed in the environment locally and globally through various processes. Atmospheric emissions of mercury can enter the environment through deposition onto soils and water. When mercury enters fresh water bodies and the oceans, or settles into sediments and soils, it can become involved in biogeochemical cycles, be transformed into the highly toxic form of methylmercury, and bioaccumulate in the food chain. Predatory, freshwater fish species such as pike, bass and walleye have also been know to attain elevated methylmercury that may be almost completely absorbed by human or animal consumers. The poster on the right shows the relative levels of mercury found in fish you catch in the waters of Vermont and fish you buy at your local grocer (see press release "State Departments Work Together To Educate Vermonters About Mercury"). Copies of the poster can be obtained by clicking on one of the two links on the right or by calling 800-974-9559 or, make your request via email. While fish consumption is the main source of exposure to methylmercury,

the Vermont Department of Health advises that the benefits and risks

of eating fish should be balanced, since fish are an excellent source

of high-quality protein and omega-3 fatty acids, and are low in

saturated fat. In order to protect Vermonters from mercury poisoning,

the Health Department issues fish

consumption advisories Although the Vermont Department of Health does not issue advisories on commercially caught fish species such as salmon, cod, pollock, sole, shrimp, mussels, and scallops, these species generally have lower mercury levels and are therefore considered safe for consumption. Other commercially available fish such as shark, swordfish and fresh or frozen tuna, generally have higher mercury concentrations. Canned

"white" tuna has been found to have a higher mercury concentration than canned "light" tuna (see the poster above for

relative mercury levels in locally caught and commercially caught fish). The U.S. Food & Drug Administration and the U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency are for the first time developing a single uniform advisory covering commercially caught fish and a draft

version of the advisory Other Human Exposure Pathways to MercuryInhalation Based on available science, normal ambient air concentrations of mercury vapour, averaging 1.6 nanograms per cubic meter of air, do not appear to be a cause for concern (1 nanogram = one billionth of a gram). Dermal Contact Dermal contact is also a route of exposure to mercury with alkyl mercury compounds being particularly notorious. While few Vermonters come into direct contact with mercury or its compounds, skin absorption can be lethal. In 1997, a researcher named Karen Wetterhahn, from Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, died when a single drop of dimethylmercury passed through her protective latex glove and through her skin. MetabolismWhen an individual is exposed to mercury, a certain percentage is absorbed, depending on the route of exposure and the form of the mercury. About 80% of elemental mercury is absorbed when inhaled, however less than 1% of ingested liquid mercury is absorbed. Methylmercury, on the other hand, is readily absorbed irrespective of the exposure pathway. Approximately 95% of ingested methylmercury is absorbed, and absorption through the lungs and skin is also believed to be quite high. Both elemental and methylmercury can cross the blood-brain and placental barriers. The critical target organ for elemental mercury is the adult and fetal brain, and the critical target organs for methylmercury are the brain and the kidneys. Inorganic mercury compounds do not readily migrate through the blood-brain or placental barriers, but do accumulate in the kidneys. Absorption of inorganic mercury varies with the type of inorganic salt. Within the body, the kidneys accumulate the highest concentrations of all forms of mercury, yet mercury can also concentrate in the brain, the central nervous system, the liver, and indeed in most organs in the body. Mercury is predominantly excreted from the body in urine and feces, but usually at a slower rate than that of uptake, leading to the accumulation of mercury in living tissue. Mercury is deposited in hair as it grows, and it may also be found in breast milk. This may result in high concentrations in infants whose mothers are heavily exposed. The unborn child also receives some of the maternal mercury body burden because mercury compounds cross the placental barrier, yielding equal or higher blood concentrations in the fetus than in the mother.

|

|

|

||||||||

|

MERC Home | mercury facts | mercury

in fish | environmental concerns | statutes & regulations

| proper disposal Mercury Education & Reduction Campaign |